Abstract | PDF | UnDisciplined (Feb 2020) | Request Permissions

Multiple Narratives of Display and Heritage in Museums: Iznik Ceramics in Comparison

Simge Erdogan

Biography | Notes

Keywords: Museum, Display, Representation, Cultural Heritage

Introduction

Museum exhibitions are instruments of knowledge, power, and representation. Museums not only shape our understanding of objects but also generate multiple meanings and narratives about them. Design aesthetics and display elements play a pivotal role in these visual and written narratives, for without them, an exhibition would be nothing but a random grouping of objects in space. Display elements (i.e., the use of light, colour, space and texts) articulate different systems of knowledge and representation which not only manipulate our understanding of the exhibits, but also narrate multiple—sometimes overlapping, sometimes contesting—stories about them and their heritage. This becomes most evident when the very same objects are displayed in different museum settings. Each museum is likely to represent identical objects in its own ways and hence they are likely to create differing stories about the objects’ broader cultural meanings, past, and heritage. Yet to what extent does a museum display affect our understanding of objects and their cultural heritage?

This paper aims to understand the power of museum display in generating narratives of culture that manipulate and eventually shape our understanding of the objects. To do so, I will provide a comparative analysis of the display of Iznik ceramics in three different museums: the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and the British Museum in London, and the Tiled Kiosk Museum in Istanbul. Examining these museums’ exhibition spaces, their display elements, and design aesthetics in particular, I will identify three approaches of display: aesthetic, contextual and systematic which create alternative visual and written narratives on the very same objects’ cultural heritage. I will conclude by exploring common problematic representations in all three museum spaces, which reproduce a nationalist paradigm and form problematic links between Iznik ceramics’ Ottoman past and so-called Turkish heritage.

Iznik Ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum

When the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Jameel Gallery of Islamic Middle East finally opened its doors to the public in 2006, it sparked great interest and excitement. The new Jameel Gallery, still home to the museum’s 10,000-piece Islamic collections, replaced the former gallery which was regarded as to be “confusingly structured and poorly lit…”[1] Curated by senior curator Tim Stanley, the V&A’s Islamic Middle East Gallery features a spectacular collection of over 400 objects are brought together in order to show visitors the interconnectedness of Islamic art and its interactions with different parts of the world, including influence over other artistic traditions. Moreover, through its displays, the gallery aims to “develop interest in and promote understanding of the diversity of Islamic art and to inspire in all people, an appreciation of its beauty.”[2]

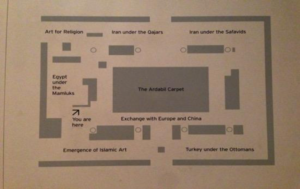

Aesthetic display refers to a tendency to highlight the beauty, uniqueness and aesthetic qualities of exhibits by presenting them, as art historian Stefen Weber suggests, “…beautifully in a clear and correct order.’’[3] Adopting an aesthetic display, the V&A’s Jameel Gallery of Islamic Middle East presents its exhibits, including Iznik ceramics, as beautiful and unique artworks of Islamic Art.[4] Accordingly, the exhibition space is divided into seven thematic sections: the first three refer to crucial themes in Islamic Art,[5] while the other four explore key regions and dynasties of the Islamic Middle East (fig. 1).[6] These four geographic regions are divided into multiple subsections, each exploring different artistic and decorative styles present in these dynasties, and convey different versions in style and decoration of each object. The thematic and stylistic organization of the space are enhanced with design aesthetics which illuminate the visual and aesthetic qualities of the beauty of the objects on display.[7] As the V&A’s Summative Evaluation Report suggests, the Jameel Gallery’s layout succeeds in communicating the key messages and the main themes of the exhibition to visitors. Half of the visitors interviewed were able to identify different artistic and decorative styles present in these dynasties “as well as various forms of art displayed in the gallery.”[8]

In this arrangement of the Jameel Gallery, Iznik ceramics are exhibited in the Turkey under the Ottomans section, which contains ten sub-sections. Quite expectedly, each one of these sub-sections explores a different artistic style in Ottoman Art between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. The museum’s Iznik ceramic collection is distributed amongst two main sub-sections: Iznik ceramics after 1550 and Iznik ceramics before 1550. The main idea behind this organization is to highlight the changing technical qualities (referring to the shift to polychrome tiles after the 1550s) and the emergence of novel designs (referring to the emergence of a distinctly Ottoman repertoire of floral designs before and after the 1550s) in the production of ceramics.[9] Looking at these sub-sections more deeply, the after 1550 sub-section includes two wall-mounted display cases, which exhibit thirty-one objects (fig. 2). These exhibits are divided into three parts with two shelves against a black backdrop that is sparingly lit with internal lighting hoods.

The before 1550 sub-section exhibits the ceramics in a freestanding glass case which includes a group of nine objects and one mosque lamp (fig. 3). They are put against a white backdrop and lit individually. All objects stand on a dark blue platform which creates a visual unity with the exquisite blues and whites in many of the ceramics. The choice of dark blue also encourages visitors to recognize—and hence explore—the defining characteristics of this particular period of Iznik ceramic production; the absence of under-glaze decoration in red and a dominant blue and white colour palette. Through this curatorial decision, the Jameel Gallery not only creates a more aesthetically pleasing visual experience but also succeeds in drawing the visitors’ attention to some defining features of Ottoman ceramic production of the period.

While the objects in the two sub-sections are exhibited in groups, there are two pieces that are displayed individually. The first, “Basin with Golden Horn Design”, is placed in a freestanding case with a glass top and placed in the middle of the room. This is the first object that visitors encounter when they enter the gallery from the museum shop (fig. 4). The second object, “A Vase with Flowers”, is exhibited in a wall case above the main introductory section panel. These individual exhibits have similar design aesthetics to those previously discussed. The Basin is placed in a glass case, standing on a black platform and internally lit from below. The Vase, on the other hand, is put against a black backdrop and lit individually. The overall colour of this display is dark blue, again a curatorial decision which highlights the exquisite blues and whites on the object (a feature that also indicates that this object was produced before 1550). Through these individual displays, the gallery presents these two exhibits as dramatic and eye-catching treasures of a collection. Moreover, through the use of individual displays, the Jameel Gallery makes many viewing angles possible by “facilitating the optimum viewing of each individual work.”[10] The gallery allows a more careful examination of the objects, and hence admiration and appreciation of their beauty, style and technique.

Aesthetic Masterpieces

Through aesthetic display, the Jameel Gallery narrates a story of the emergence and evolution of the art and style of Iznik ceramics. This narrative is conveyed first by a visual storyline which focuses on a stylistic evolution of ceramics and second by stylistic sub-section divisions and object placements, which present ceramics as beautiful works of art to be aesthetically appreciated.

As visitors move from one sub-section to another, they follow a visual narrative which focuses on the evolution of a distinct style in the arts of ceramic production. The key and carefully selected location of display cases make this possible. For instance, Iznik ceramics before 1550 sub-section exhibits a mosque lamp (a key object that signals the emergence of distinct style and early experiments with the colour red to underglaze decoration) in the left corner of the display case (fig. 5). Putting this mosque lamp at this corner forms a visual unity between this section and the following Iznik ceramics after 1550 sub-section. When visitors move to this next section, they see later examples of under-glaze decoration in red, which represents the evolution of style, the expansion and the rise of quality in color palette, and variation in shapes and design. By linking one section to another, visitors are encouraged to follow the evolution of the style of ceramic production.

While narrating the story of the evolution of ceramic production and distinct style in Iznik, the gallery also narrates a story of cross-cultural stylistic and artistic interactions between Iznik and other regions. This is made possible through space layout and thematic section divisions. To convey the message of cross-cultural influences on Iznik production, the Iznik ceramics before 1550 sub-section is placed between the Exchange with Europe and China section on the right and the Iznik ceramics after 1550 sub-section on the left. To complement the story, early examples of “blue-and-white ware” ceramics (which reflect Chinese influences) are placed towards the right corner of the display case closer to the Exchange with Europe and China Section. Likewise, the Iznik ceramics after 1550 sub-section is placed next to the Safavid Ceramics section (fig. 6). Through this, the gallery communicates one of the main messages of the exhibition: “Ottoman and Safavid styles are different but have a shared origin and shared characteristics.”[11]An example of these shared characteristics is the colours, designs, and glazes of Chinese ceramic work that was an important source of technical and aesthetic inspiration for both the Safavid and Ottoman ceramic production. The visitor responses indicate that the gallery is successful in conveying cross-cultural influence and allowing visitors to make connections between Iznik and other ceramic production centers. Of those interviewed, six visitors reported that the gallery showed them the influences of Islamic art such as its fusion with the west, influenced by China, influences on other parts, and influences on European art.[12]

Iznik Ceramics at the British Museum

Between 1989 and 2018, the John Addis Gallery of Islamic World was home to the world’s largest Iznik ceramics collection and the British Museum’s world-renowned collection of Islamic World art, artefacts and contemporary artworks from vast territories including Levant, North Africa, Central Asia, and Turkey. In October 2018, the John Addis Gallery was replaced by the newly refurbished Albukhary Foundation Gallery of Islamic World.[13] Opened its doors to the public after an ambitious four-year project, the new gallery reflects the museum’s aim to present its collections in new and creative ways and show visitors more of the cultural diversity of the region.[14] As the British Museum’s first gallery devoted to the art and culture of the Islamic world, the John Addis Gallery still entices a remarkable example for the power of museum display and representation. It was an important space which adopted an alternative mode of display and representation in the display of Iznik ceramics. In contrast to the V&A’s Jameel Gallery where an aesthetic approach is embedded in the thematic arrangement of sections and stylistic arrangement of sub-sections, John Addis Gallery adopted a contextual approach that was reflected in geographical-dynastic organization of space and chronological placement of objects in display cases.[15]

The main aim of contextual display is to bring to light the historical and cultural context of objects that “evoke the original contexts from which museum objects were taken.”[16] Accordingly, space was divided into two geographical sections: the Eastern Islamic World (such as Iran and Central Asia) and the Western Islamic world (such as Egypt, Sicily and Turkey). To narrate the history of each geographical region, these sections were further divided into dynastic sub-sections that are organized around chronologies.[17] In contrast to the dark and sparingly lit atmosphere of the Jameel Gallery, which puts emphasis on objects’ visual and aesthetic qualities, the John Addis Gallery exhibited objects in groupings contained in display cases that are divided by shelves. The gallery, as well as display cases, were well lit with both natural light and with integral yellow hoods. This created an intimate atmosphere within the space via the use of warm colours.

The John Addis Gallery’s contextual display built a context, a history and a story around objects, which “told [a] bigger story about cultures, people and cultural history.”[18] Accordingly, ceramics were presented in this space using “rigid dynastic periodization”[19] and a highly chronological order. Iznik ceramics featured in three sections, each represented by a display case. The first section was the Ottoman Empire section, which was located on the left-hand side of the main space towards the back of the gallery (fig. 7). The second and third sections were Iznik Pottery 1520s–1530s (fig. 8) and Iznik Pottery 1550–1560 (fig. 9) respectively, which stood in front of the window.

Turkey under the Ottoman Empire Section (August 2015, image courtesy of author).

The dominant contextual logic behind the display of objects in the John Addis Gallery was also reflected in its design aesthetics. In contrast to the V&A displays (which use a combination of different colour backdrops and design materials such as platforms and shelves), the John Addis Gallery adopted an aesthetic unity in its presentation: all objects were put in glass cases that use no backdrop, enabling visitors to see the samples from all sides. The well- and internally lit display cases had a yellow colour, presented objects in groupings and equally distributed them amongst the upper, middle and lower parts of the cases. These presentation choices reflected a concern to draw visitors’ focus to the context, rather than individual qualities of objects.

Artifacts of Material Culture

In contrast to the Jameel Gallery’s story of the evolution of ceramic production and style of Iznik as works of art, the John Addis Gallery narrated a different story that was based on the history of Iznik ceramics. This was made possible by a variety of curatorial decisions: first by the geographical ordering of space and chronological placement of objects, which brought to light multiple contexts in which objects were embedded and produced; and second by the use of texts that placed focus on the materiality of objects over their artistic qualities.

The John Addis Gallery’s geographical section divisions and chronological object arrangements revealed an aim to contextualize and historicize Iznik ceramics. The gallery’s visual storyline showed visitors multiple contexts in which Iznik ceramics are produced. As visitors moved within the space, they followed a narrative that is concerned with the different roles that ceramics played in past social, cultural and artistic contexts. These contexts included changes in visual qualities, cross-cultural interactions between Iznik and other ceramic production centres and the rise of the quality and technique of the products. Starting from the main display case, Pottery of Iznik, visitors were encouraged to explore the history of Iznik ceramics within these multiple frameworks (fig. 10). The first display case presented the history of Ottoman Empire whereas the next section, Iznik Pottery mid-sixteenth century, introduces Chinese influences on Iznik ceramics (fig. 11). Accordingly, as visitors moved from one display case to another, they explored “many qualities of artifacts that are important for specific place[s] in particular social contexts.”[20] The use of a contextual and historical approach to display not only allowed visitors to embed Iznik ceramics within the broader history of Ottoman Empire and the heritage of ceramic production, but also placed an emphasis on ceramics’ materiality over their visual and aesthetic qualities.

View of main display case featuring Pottery of Iznik (left) and display case featuring ceramics from 1520¬–1530 (right) (August 2015, image courtesy of author).

Iznik Ceramics at the Tiled Kiosk Museum

Tiled Kiosk Museum. Main hall (June 2015, image courtesy of author) The Tiled Kiosk Museum is a public museum located in Istanbul, Turkey. It exhibits its Iznik ceramics collection in a one-store museum building which consists of the main hall and five side rooms.[21] Behind its exhibits and design is a systematic display, which refers to “the grouping of objects by means of any number of conceptual categories.”[22] This display approach reflects an aim to expose visitors to the range of artifacts on view, and hence encourage their exploration and discovery. This becomes most evident in the spatial organization and design aesthetics of the exhibition space, which inform us about a variety of attempts for classification and systematization. Accordingly, Tiled Kiosk displays are organized in multiple ways that articulate multiple systems of knowledge and organization which incorporate themes, styles and techniques together. In contrast to the V&A and British Museum’s exhibitions where sections are divided into subsections that explore different themes, we do not see any sub-sections at the Tiled Kiosk. Rather, the exhibits are placed in six key sections. Three sections, Miletus Ware, Blue and White Ware and Polychrome Ceramics, are placed in the main hall and explore different techniques of ceramic production in Iznik. Two sections explore other ceramic production centers, Kütahya and Canakkale Ceramics, that emerged in the Ottoman Empire and one section explores the Seljuk ceramics. These sections are placed in three side rooms.

When we look at the placement of exhibits within display cases, we see a combination of both groupings and individual displays. Some exhibits are presented in groups in freestanding display cases while others are exhibited individually in wall cases (fig. 12). Similar to the British Museum, Tiled Kiosk has a well-lit atmosphere. Its objects are put against white walls of the gallery and lit internally with lighting hoods on the upper part of the cases. The main hall and rooms of the Tiled Kiosk have an intimate atmosphere created with the use of warm colours and lighting.

Iznik ceramics at the Tiled Kiosk feature in four sections, three of which are placed in the main hall and one in a side room. The majority of ceramics in the main hall are exhibited individually or in a composition of two-three objects in wall cases along the walls of the hall. In one display case that stands at the center of the main hall, there are six objects exhibited in groups. Another display case, placed between doors, exhibits a total nine objects (fig. 13). Through the use of lighting, the overall colour achieved in their displays is light green, a colour that creates low level of contrast in the space. Through this, the gallery creates a bright and unified space which places an equal emphasis on objects on display and “draws in the visitor and allow them to explore the area as a whole.”[23]

The groups of samples, on the other hand, are brought together to explore the style and technique of their production, and diversely placed inside display cases, well-lit with internal lighting hoods that have an overall yellow colour (fig. 14). Recalling the Tiled Kiosk’s main objective is to show visitors the range of objects (by placing emphasis on their categories based on types, styles and techniques), the exhibits in this museum have no chronological concerns. This is in contrast to the V&A and British Museum displays. The non-chronological placement of objects reflects intentions to classify objects according to their style, production and technique rather than their histories.

Authentic Objects

The Tiled Kiosk’s systematic display narrates a different story when compared to the previous museums. The storyline at the V&A focuses on the emergence and evolution of the ‘art’ of ceramics, while the British Museum prioritizes the ceramics’ historical context. With an intention to show visitors the range and originality of objects, Tiled Kiosk’s narrative is concerned with the ‘authenticity’ and ‘making’ of ceramics. In other words, the gallery presents them as authentic cultural products of Turkish nation that can be seen as both works of art and functional objects which can be appreciated for their originality, variety, technique, and types. The words ‘authentic’ or ‘authenticity’ in museums usually refers to a piece of art or object that has a proven and undeniable provenance to an original maker, producer, or artist.[24] It has an undisputed origin, it is genuine, and original. Looking at the Tiled Kiosk displays from this perspective, attaining an authentic value to the displayed ceramics can be seen as an attempt to turn them into ‘original’ products that can (undeniably) be traced back to certain context, time period, and more importantly, to their maker; in this case the Turkish nation.

As visitors follow different sections, they explore the ‘originality’ and ‘authenticity’ of the ceramics. Starting from the main hall, visitors first explore the objects’ aesthetics, decoration, and style, followed by the story of multiple techniques and production in Iznik. Visitors are encouraged to explore the ‘uniqueness’ of ceramics on display through this organization based on technique and production. Texts and labels accompanying objects also play a key role in systemizing objects and presenting as authentic objects of Turkish nation that can be seen as both works of art and functional objects. Through use of language, an emphasis is placed on the technique and production of objects, and this suggests an attempt to show visitors the displayed objects’ importance and value and encourage them to see these objects as products of Turkish culture.

Ottoman vs. Turkish? A Common Nationalist Paradigm

Although the three museums represent Iznik ceramic differently—as artworks, artifacts and authentic objects, and narrate different stories about their heritage—they all form problematic links between their Ottoman past and so-called Turkish heritage. That is to say all three museums, and their respective narratives, form a cultural and artistic lineage between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. In doing so, the museums create an illusion of uniformity and uninterrupted culture. This representation reconstructs the nationalist paradigm that has become popular since the decline of colonial influence in the nation states of the Islamic Middle East and in the field of Islamic art.[25] Developed by a joint group of native and foreign authors both in the West and non-West, this paradigm approaches and explains a variety of Islamic art and culture through national character traits.[26] More concisely, it takes modern nations as its starting point in its construction of some geographical continuities in the arts with these nations’ predecessor empires and states.

As the analysis of display elements and design aesthetics showed, The V&A Jameel Gallery frames Iznik ceramics within the category of Ottoman arts and design. Exhibited under the Turkey under the Ottomans section, Iznik ceramics are merely placed within Ottoman artistic and cultural heritage. Interestingly, by doing this, the gallery also forms some links between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, as well as between the ceramics’ Ottoman and Turkish heritage. Using the notion of ‘Modern Turkey’ and ‘Turkishness,’ which was invented in the late eighteenth century as a point of reference for sixteenth-century objects, the gallery reconstructs the nationalist paradigm that is present in Islamic Art and history, which creates an alleged cultural, historical and artistic uniformity between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. While some captions present Iznik ceramics as elements of Ottoman artistic and cultural heritage, which represent “Ottoman art” or the “taste of Ottoman court”, others refer to them as elements of “Turkish fritware”, as seen in a caption taken from the final paragraph of the introduction panel of Iznik ceramics after 1550 sub-section:

From the 1590s, standards declined as court patronage receded. The final phase of Turkish fritware production was initiated by Sultan Ahmed III (ruled 1703-30)

These samples are referred to as “Turkish fritware” rather than Ottoman fritware, even though the final ceramics commissions were made by the Ottoman court in an eighteenth-century context during the rule of Ottoman Empire.

Likewise, the British Museum’s John Addis Gallery reconstructs a similar nationalist paradigm. Although the John Addis Gallery contextualizes its exhibits within the geography and history of the Ottoman Empire, it still represents them as artifacts of Turkish material culture. This creates an inconsistency between the gallery’s storyline and object labels. While the former is excessively concerned with the history of objects within the Ottoman Empire, the latter predominantly interpret them as Turkish. Starting from the beginning of the Ottoman Turkey section, visitors encounter a narrative which presents Iznik ceramics as cultural products of Turkish heritage. Indeed, the main introductory panel of the Ottoman Empire section, tells visitors (with a nationalist viewpoint) that “Ottomans were Turks in origin who established themselves in Asia minor and raided Byzantine territories from about AD 13000…” Another good example that elucidates the nationalist paradigm is the caption from the label of the object entitled as “Large Footed Bowl”: “This uniquely Turkish form is known as a tezza. Few survive, but they were very popular as can be seen by their depiction in Turkish miniatures of the time…”

Finally, when we look at the Tiled Kiosk’s narrative, we see similar nationalist tendencies. The Tiled Kiosk Museum, however, takes this paradigm a step further and represents its exhibits as ‘pure’ products of Turkish cultural and national heritage. In the V&A and British Museum, Iznik ceramics are placed within the broader category of “Islamic Art” and “Islamic World” which represent a conceptualization conversant with the Orientalist tendency to generalize all arts that were produced under predominantly Muslim dynasties as Islamic. The Tiled Kiosk, on the other hand, places Iznik ceramics in a nationalized Anatolian geographical context. Following the paradigm of Turkish nationalist history writing, the museum presents a story of uninterrupted Turkish cultural heritage. To achieve this, certain aspects of Iznik production which were present both at the V&A and British Museum—such as the cross-cultural interactions and artistic exchanges between Iznik and other production centers—are ignored in the space. Likewise, the gallery also ignores the historical background of objects. It neither mentions the history of the Ottoman Empire nor makes any references to Iznik ceramics’ broader place within Islamic art and heritage.

This focus on “our” art and architecture can be seen as a reflection of the national art history of Turkey.[27] Nasser Rabbat suggests that after the breakdown of Ottoman Empire, Turkey experienced radical rupture with the past that paved the way to the rise of national art history, which selects pieces of Islamic art and segments from the Ottoman past as its own and connects them to the history of a nation.[28] Although the two museums in the United Kingdom (the V&A and British Museum) intend to reveal the diversity, variety or cross-cultural influences of Iznik ceramics and their heritage, they still adopt a narrative based on nationalist art history which assumes an uninterrupted cultural continuity between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. The Tiled Kiosk Museum display, on the other hand, reflects this nationalist paradigm in its entirety, neglecting the Ottoman past and cross-cultural influences, and taking modern Turkey as a starting point of reference for objects’ heritage.

Conclusion

This comparative analysis of the display of Iznik ceramics at the V&A, British Museum and Tiled Kiosk reveal different, aesthetic, contextual and systematic modes of display. Once these three visual representations come together with visual and written stories created by texts and labels, they generate three different narratives of the heritage of Iznik ceramics. Accordingly, the same objects become unique works of art of artistic heritage at the V&A. At the British Museum, they become artifacts of material culture which have important historical and geographical values. Finally at Tiled Kiosk, they become authentic and unique objects of national heritage. Hence, although coming from the same city, same socio-cultural background and time periods, the very same objects are ascribed different cultural meanings.

The study and comparative analysis of Iznik ceramics in three museums also reveals the reflection of the nationalist paradigm which is still present in museum exhibitions and displays. Although each aforementioned museum chooses how to display the ceramics and selects how to narrate them, they all form some problematic links between the objects’ Ottoman and Turkish heritage. Emerging literature and current museum practices recognize museums as cultural institutions that shape our understanding of Western and non-Western objects and cultures. As such, Iznik ceramics become an interesting case that illustrates the legacy of the national paradigm, which evidently is still alive both in the Western and non-Western museum practices.

The multiple representations of Iznik ceramics and their heritage evince a remarkable example that indicates the power of museums in the construction of knowledge about objects. The comparative analysis of Iznik ceramics reveals the complexities and potentials of the museum representation by articulating three different modes of display which generate three alternative narratives on Iznik ceramics past, value, and heritage. Through the lens of Iznik ceramics, we get a chance to unfold some written narratives, visual storylines, and curatorial decisions which play a pivotal role in shaping our understanding of the objects. Once we discover this close relationship between museum displays and representation, we start to ask new critical questions about museums, their spaces, and curatorial decisions. This allows us to ask some questions about how our experiences are shaped, and sometimes manipulated, by museums, and by various display methods that are adopted in their exhibition spaces. When framed in different museum spaces, the same object that we saw, engaged with, and admired before can indispensably be interpreted in multiple, rather divergent ways. Yet, the objects that museums put on display are very likely to create different visual and aesthetic experiences, acquire new cultural meanings and generate alternative stories. This is how they become a constitutive part of the broader story that museums choose to tell us. The story of Iznik ceramics is the story of the people, empires, and nations that created them, it is the story of the cultures and interactions that they represent, and more broadly, it is the story of the world that created them, as well as the world that houses them, which is the same world that surrounds us.